The Solution Is The Problem

- Marco Annunziata

- Jul 9, 2021

- 5 min read

Governments are saving the world. Again.

Nearly everyone credits governments for saving the world from a new Great Depression. Rightly so, maybe. With factories shut down and people locked up, governments stepped in with a wide array of generous subsidies; then, as economies reopened, they launched the most ambitious public spending plans we’ve seen in our lifetimes. The US has done it on a gargantuan scale, but Europe has also broken new ground with unprecedented stimulus.

It’s becoming a habit, this saving the world thing. Governments had barely finished bringing the world economy to safety from the Global Financial Crisis, and they had to jump in again.

Central banks have again been right by their side. Ten years ago they played the primary role, leading the charge while governments mustered the courage to spend. This time politicians needed no encouragement, and central banks have taken a supporting role, flooding markets with liquidity and dreaming up creative schemes to support specific sectors of the economy.

Emboldened by their success, policymakers are now taking on loftier goals, with plans to revamp infrastructure, save the environment, fight inequality and discrimination, reinvent social safety nets and relaunch scientific progress with new investments in R&D and innovation.

This ambitious and far-reaching government plans have been widely welcomed and applauded. Some economists believe that governments have always been the primary engine of innovation. Mariana Mazzucato of University College London argues that pretty much any innovation worth talking about can be traced back to the government. From the internet to every single component of the iPhone to electric vehicles, they were all made possible by a government-sponsored research program or a government subsidy.

Governments have repeatedly saved us from imminent economic disasters and are now setting out to save us from longer-term existential threats while laying the scientific basis for greater, equally shared prosperity. So what if they’ve occasionally stopped you from going to a restaurant, opening your shop or taking your dog for a walk?

Except… Take a more critical look, and you realize that the response to the pandemic has been horribly mismanaged. Governments have been unable – or unwilling – to protect the elderly. Under cover of the “follow the science” mantra they have imposed a litany of superstitious rituals and arbitrary restrictions. The lockdowns of entire economies are what caused the economic disaster in the first place – with dubious efficacy in containing the virus and tremendous costs for the economy and broader public health (several studies have failed to find a relation between lockdowns and mortality; The Economist offers a fairly balanced discussion of the costs and benefits of lockdowns). To top it all off, scientists and public officials now admit that the virus could have originated in a government lab in the first place – which I guess would confirm that indeed every life-changing innovation can be traced back to the government.

In other words, governments caused the problem in the first place. Much like in the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, come to think of it. The leverage bubble in financial markets was enabled by loose monetary policy while central bankers patted themselves on the back for having achieved the “Great Moderation”, a brave new world of low inflation and no recessions. The ludicrous excesses in the US housing market, at the heart of the financial crisis, were aided and abetted by policy makers and regulators (as noted by Raghuram Rajan, former IMF Chief Economist and former Governor of the Reserve Bank of India, in his 2010 book Fault Lines).

You could see it as an example of Say’s Law, where “supply creates its own demand”: the supply of government-caused crises creates its own demand for government-led rescues.

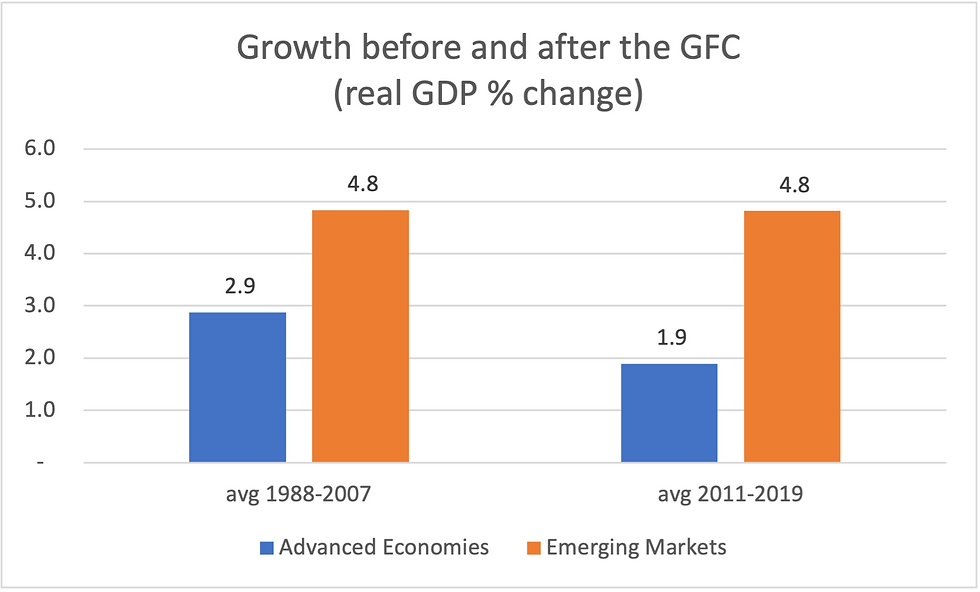

Whether the rescues themselves should be rated a success is another question. The GFC was followed by a famously anemic recovery, with sub-par economic growth, a slow pick up in employment and languishing productivity growth. GDP growth in advanced economies was about one-third lower after the GFC than before, while emerging markets marched on at the same pace. The current recovery appears robust for now, but it’s hobbled by a long wave of supply disruptions and shortages, courtesy of the prolonged restrictions on activity, and in the US by a lack of workers, courtesy of generous unemployment benefits. We still face shortages of basic products, from automobiles to home appliances – only the good old Soviet Union did a better job at causing shortages and rationing.

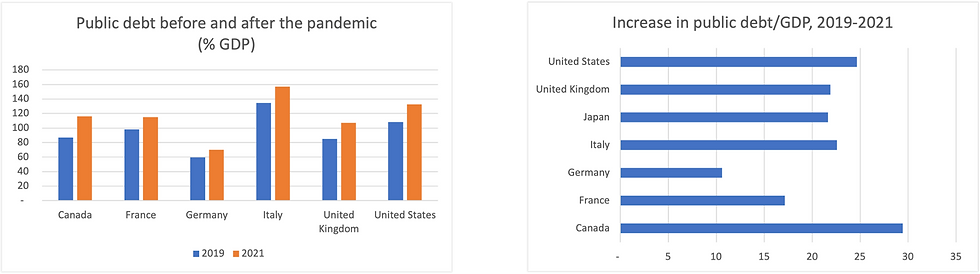

Large government spending plans have earned near-unanimous applause; why shouldn’t governments spend liberally on multiple priorities when they can borrow for free? Public debt is set to rise by 20-30% of GDP in just two years in most G7 countries (latest IMF data; the notable exception is Germany). The problem is that these plans carry massive hidden costs. When interest rates eventually rise, bloated public sector debt levels will become much more costly. Meanwhile, the outsized role of central banks in financial asset markets has created a situation where investors are quick to panic if central bankers as much as clear their throats.

What worries me most is that democratic governments across the world have gotten a taste of emergency powers – and loved it. The Covid-19 emergency has been used to justify unrestrained government intervention in the economy, unthinkable restrictions on individual liberties, and unacceptable shutdowns of public debate on several important issues – including the de facto censorship of any scientists challenging officially approved views. And by a large, the citizenries have accepted all this with barely a grumble.

The same politicians have already made it clear that we still face a number of existential emergencies. A new Covid-19 variant is always around the corner. Climate change, of course. Inequality. The US government has now acknowledged UFO sightings, so how about the threat of alien invasion? Any one of these threats could wipe us out, and once again, only governments can save us, so how will we object to whatever new interventions and restrictions they decide to announce? A permanent state of emergency justifies permanent emergency powers.

But emergency powers imply weaker accountability, which opens the door to very poor decisions.

Massive government spending and far-reaching regulations distort incentives, and will eventually require commensurate tax increases. Some previous government efforts to tackle “existential threats” backfired in embarrassing ways – European governments encouraged and subsidized diesel engines for many years in the conviction that it would help the climate.

Yes, government-funded research programs, mostly linked to the military, have provided the initial spark for many valuable innovations. But certainly not all. And it’s private enterprise that has translated those initial sparks into the products and services we actually use. When the private sector has the space and the resources to innovate, government contributions to research can be very helpful. But they can’t replace the private sector. Otherwise state-dominated economies would always have been the most innovative. North Korea did not create the internet or the iPhone. The latest, impressive breakthroughs in space research have come from private companies. In California, Space X has successfully developed reusable rockets; the government has not been able to build a high-speed train link between San Francisco and Los Angeles after thirteen years of efforts.

Yes, governments have twice stepped in to save us from economic disasters; but government policies helped cause those disasters in the first place. Before we unquestioningly embrace a bold new era of bigger government intervention, let’s take a closer look at the track record of the policy makers we are entrusting our lives to.

What looks like the solution is in fact the problem.

Comentarios